Badwater Double Crew Report

“As you all know, crewing is much more difficult than running this course,” announced Jared, one of the Badwater Ultra officials, at a pre-race meeting.

Despite the people around me nodding their heads in agreement, it seemed like an outlandish statement that Charlie Sheen would make. Supporting a racer is harder than traversing 135 (or in Alene’s case, 270) miles on foot? He might as well have followed that up with a proclamation that carrying golf clubs for Tiger Woods is more difficult than winning the Masters, or that a ball boy’s job is more tiring than smacking tennis balls while looking pretty like Anna Kournikova.

Of course, this was before I knew that crews would typically have to stop and offer their runner assistance literally every half mile. And in our case, for six whole days.

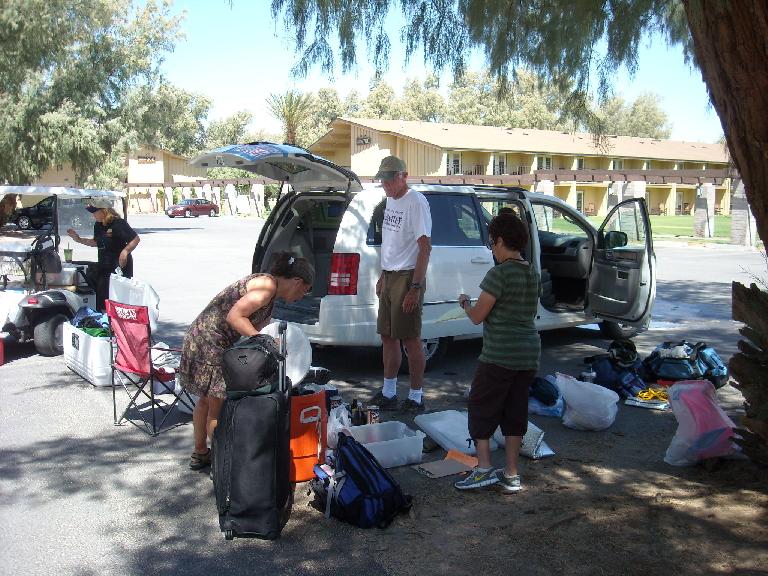

The first day in particular was particularly frenetic because Alene was moving at her fastest (13-18 minute miles); the day was the hottest (as much as 110 degrees); this was the first time Ed, Steph and I were working as a crew; and because we had Way Too Much Stuff. In addition to $400 worth of Walmart goods, the van was loaded with 250 pounds of water and 150 pounds of ice at the onset. While the H20 was essential, most of the rest of the stuff usually just got in the way and caused us to work extra frantically, especially when Alene wanted something A.S.A.P.

Some of the stuff we had to hand off every 0.3-0.7 miles included head ice, neck ice, ice water to drink, and a mixed drink. The latter was more time-consuming than you’d think because it would require tearing open a Crystal Light packet and pouring its contents into a bottle, opening two S-caps and dumping its electrolytes into the mix, then adding ice and water. If we prepared the bottles too far in advance, some of the ice would have melted and then we would be told the drink was too dilute or did not have enough ice.

Food was another issue. While we had plastic bins and coolers with enough food to eliminate starvation on a small island, we sometimes did not have or could not find items that Alene wanted at that moment. She was about as particular in her cravings as a pregnant woman and substitutions were not allowed (e.g., no pretzels instead of Pringles), so there were a few cases when we had to point the van in the other direction, speed off towards the nearest store, and return with the requested goods.

Then there was the challenge of sleep. We had five crew members for the race but only three for the return trip, and ultimately all crew members averaged about five hours of sleep per day. (Of course, Alene slept even less.) While five hours wouldn’t sound bad at all to Barack Obama or Donald Trump, there was a stretch where Steph and I went 36 hours straight without sleep, which transmogrified us into zombies. In hindsight, it might have been better if we had skipped the first two out of three hours of the post-race party and slept instead, especially if we were more serious about going up Telescope Peak—something we ultimately did not have enough time for.

Within the 36-hour sleepless stretch, however, was the most memorable part of the journey for me. Alene—who was ahead of goal pace for the first 24 hours of the race—was starting to lag due to sleepiness, blisters, and a 1+ hour visit with the foot doctor to take care of them. Therefore, I accompanied her the last 23 or so miles to the finish line at Whitney Portal to help ensure she’d remain safe and finish ahead of the 48 hour time limit.

The evening and night was gorgeous, starting with a crimson sunset over Mt. Whitney in the distance and a nearly full moon rising from the opposite direction. Temperatures were very comfortable and with Lone Pine seemingly within shouting distance, the spirits of everyone were up. Alene seemed particularly cheery, perhaps due to the knowledge that she was going to finish the Badwater Ultra race for the second time in the early morning.

Then she started sleepwalking.

The first sign of it was when she started wandering towards the yellow line in the middle of the road. Each time I’d put my hand on her right shoulder and ease her back to the left side of the road, but there were a few times she’d start giggling and exclaim, “I’m weaving!”

Not long after this, she started pointing at shrubs to the left of the road. “SEE?” she at one point asked. At first I didn’t understand, but it soon became clear that she was hallucinating—especially after she muttered, “Pacman.”

Not seeing Pacman (or chasing ghosts) anywhere I remained befuddled, but didn’t have her elaborate. Besides, she was quickly out of her Pacman phase… and into a SpongeBob one.

“Those things look yellow, like SpongeBob!” she said. She was particularly disturbed by the bushes’ shadows, which looked like claws reaching out for her. I assured her that these bushes were “peaceful” and “nonviolent” so weren’t anything like SpongeBob, but she remained unconvinced.

Meanwhile, another racer and his pacer caught up to us and were easily within earshot. They were having a serious discussion about race strategy, and the contrast in our conversations was striking.

Them, to each other: “What do you think about 20 minutes of sleep in Lone Pine before we make the final push?” “If we do so, there will still be X hours remaining, meaning that we’d have to go X miles an hour, or X minutes per mile. It’s doable.”

Myself to Alene: “Nono, SpongeBob is rectangular! These bushes are round. Besides, SpongeBob wouldn’t even be in the desert—it is too dry for him. Sponges like moisture.”

I don’t think I fully convinced Alene that SpongeBob was truly not out there, but I consider my attempts to do so were some of my greatest contributions to her race.

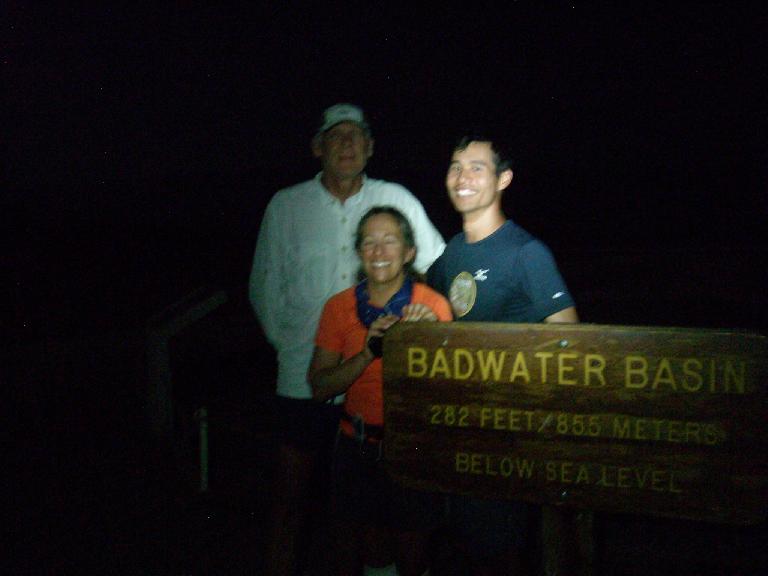

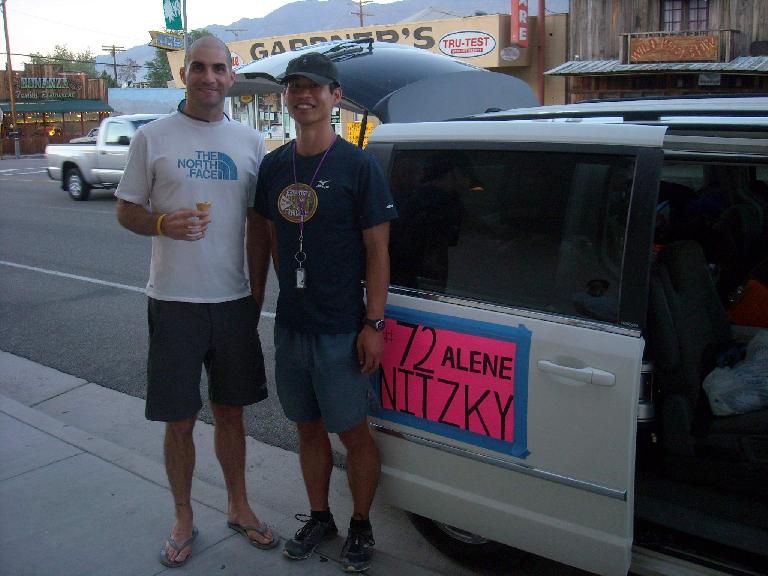

Alene finished the Badwater 135 in 45.5 hours (77th out of 94 starters, including 11 DNFs), or 1 hour 34 minutes faster than her 2008 time. She completed the return trip another 94.3 hours later, so the entire 270-mile journey took 139.8 hours (1.9 miles/hour, or 46 miles/day). There was not enough time to climb Telescope Peak—which would have made her journey 285 miles—but it will still be there the next time Alene decides to do Badwater.

At least two other race participants opted to double, including Dan Westergaard of California and Mimi Anderson of the UK. (In the Twitter universe, at least two more stated their intentions to double, but I’m not sure if they did or not.) Mimi’s journey was particularly notable in that she also climbed up and down Mt. Whitney and arrived back at Badwater after 109 hours, breaking the women’s record by 20 hours.

Mimi did seem surprised that other people were trying to do two lengths of the Badwater-Whitney course this year, but I don’t think she was aware that ~50 have already done so (according to Alene)!

The race entry fee is an eyebrow-raising $1000—which gets you no aid stations, just officiating, a T-shirt, a belt buckle for finishing within 48 hours, pre-race tips and post-race party—and is limited to 100 racers. Most participants end up spending $4000-$10,000 for the 48-hour event. While everyone calls it a run, it is more precisely a fast hike except for the top 10 who are actually running half of the time. Think of Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikers, but without a pack, a lot more aid and 135 miles instead of 2,700—it makes the race seem less daunting.

The race is held when Death Valley is at its hottest—temperatures can reach as much as 130 degrees, although this year the heat was unusually mild—but this is severely mitigated through generous use of ice. The irony is people purportedly WANT to run through extreme heat (why else do it in Death Valley in the summertime instead of any time the rest of the year when temperatures are nice and the risk of skin cancer is lower?), but then do everything they can to stay cool via head ice, neck ice, iced drinks, and cool-downs using iced towels—luxuries not available in any other athletic event and certainly not before the advent of refrigeration and ice-making.

If all this sounds utterly absurd to you, then maybe doubling, running “solo” with assistance but as an unofficial “racer”, or (most hardcore) going solo AND self-supported/self-contained starts to make more sense. (Marshall Ulrich has done the latter and Lisa Bliss is attempting to do so this week.) At least it brings down the dollar per mile ratio and brings back some purity to this ultramarathon endeavor.

Then again, extreme events like Badwater are hardly rational. It is what makes them extraordinary, remarkable feats beyond the mundaneness of the typical 9-5 office regimen. Congratulations to Alene on her amazing accomplishment.

And now that I have survived a job “more difficult than running the course,” I am waiting to hear from Tiger Woods. I hear he needs a new caddie.

More about Alene’s Double Badwater Journey

See Alene’s blog.

![The crew of Dale Perry (who was going to commence a solo [non-race] crossing of Death Valley) stopped to say hello while Alene was going up Townes Pass.](https://felixwong.com/gallery/thumbs/b/badwater0711-41.jpg)