Mt. Whitney, CA

It was a goal I had committed myself to the instant I sent out a $15 check in February for a permit: to ascend the tallest of all peaks in the lower 48 states in one-day. I planned to do it on the Sunday of Labor Day weekend, to give myself plenty of time to drive to and from Whitney. In addition, I planned to do it solo. This way, I could go at my own pace and have some time to myself.

I drove the BMW Z3 through Yosemite to get there, stopping through Stockton to visit a friend for a couple of hours. The drive was superb and surprisingly free of traffic. The drive up took about seven hours.

However, that wasn’t the focal point of the trip; the climb was. Arriving in darkness in Lone Pine at around 8:00 p.m., I dined at P.J.’s, the local 24-hour diner, enjoying a delicious plate of pasta. Later, I lodged at a modest motel (which nonetheless charged around $65) for the night. Initially, I had contemplated sleeping in the Bimmer at the base of Mt. Whitney, 13 miles away. However, I opted to “indulge” in comfort there instead, reasoning that I would sleep better than in the Z3’s seat, which couldn’t recline back more than 120 degrees.

Time Chart

| Landmark | Distance (miles) | Altitude (ft) | Recommended Arrival Time* | Actual Arrival Time | Comments |

| Trailhead | 0 | 8361 | 4:00 a.m. | 4:30 a.m. | Started out with two folks from Southern CA. |

| John Muir Wilderness Sign | .5 | ~9000 | 4:30 a.m. | 4:50 a.m. est. | . |

| Lone Pine Lake | 2.5 | 9960 | 6:30 a.m. | 6:15 a.m. est. | |

| Bighorn Park/Outpost Camp | 3.5/3.8 | 10365 | 7:10 a.m. | 6:45 a.m. est. | . |

| Mirror Lake | 4.0 | 10640 | 7:35 a.m. | 7:05 a.m. est. | . |

| Trailside Meadows | 5.0 | 11359 | 8:35 a.m. | 7:35-7:45 a.m. | . |

| Trail Camp | 6.3 | 12039 | 9:35 a.m. | 8:40-8:45 a.m. | I ran out of water around here. |

| 97 Switchbacks | 6.3 | 12039 | 9:50 a.m. | 8:55 a.m. est. | . |

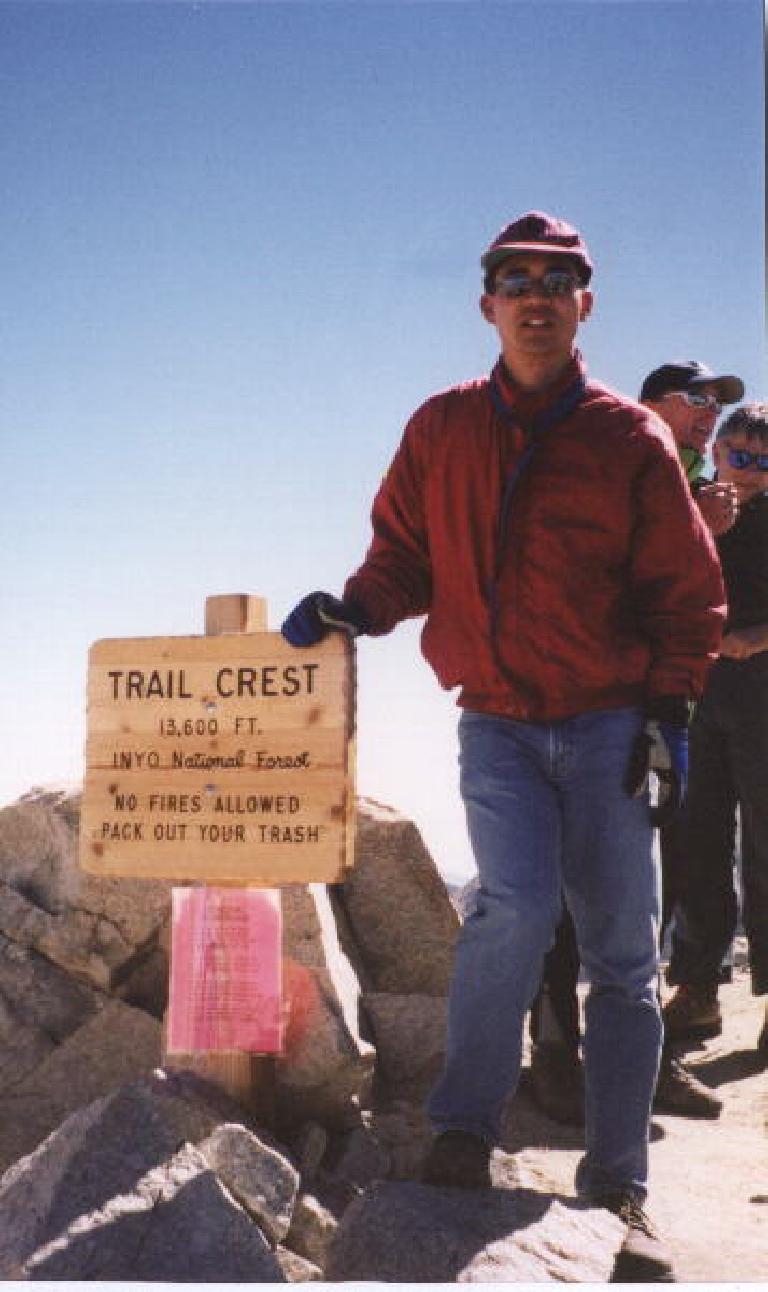

| Trail Crest | 8.5 | 13777 | 12:20 p.m. | 10:40-10:45 a.m. | . |

| Whitney Summit Trail/John Muir Trail Junction | 9.0 | 13480 | 12:35 p.m. | 11:00 p.m. est. | Shortly afterwards, a hiker coming down gave me water. |

| Summit | 10.7 | 14496 | 2:40 p.m. | 12:40-12:55 p.m. | |

| John Muir Trail Junction | 12.4 | 13480 | 4:15 p.m. | 2:30 p.m. est. | . |

| Trail Crest | 12.9 | 13777 | 4:30 p.m. | 2:45 p.m. est. | . |

| Trail Camp | 15.4 | 12039 | 6:00 p.m. | 4:15-4:30 p.m. est. | Stayed to chat with a wonderful group who gave me Tylenol. |

| Trailside Meadows | 16.4 | 11395 | 6:30 p.m. | 5:00 p.m. est. | Met Mike here and would walk with him all the way back. |

| Mirror Lake | 17.6 | 10640 | 7:10 p.m. | 5:40 p.m. est. | . |

| Outpost Camp | 19.6 | 10365 | 7:25 p.m. | 5:55 p.m. est. | . |

| Lone Pine Lake | 18.9 | 9960 | 8:00 p.m. | 6:30 p.m. est. | . |

| Trailhead at Whitney Portal | 21.4 | 8361 | 9:20 p.m. | 7:45 p.m. | Just got pitch black; made it down without needing to use lights. |

The Start

At 3:30 a.m., I woke up and almost immediately drove over to the Whitney Portal at the base of the mountain. It seemed like this short 13-mile journey had gained at least 2500 additional feet in altitude, and I began to wonder just how wise it had been for me to have stayed in Lone Pine rather than at the higher elevation. The Portal, at 8500 or so feet, was already 8500 feet higher than what my body was used to (and had been just 24 hours ago), and in another 10 hours or so, I would be 6000 feet above that.

Undaunted, I found a parking spot and was ready to start climbing by 4:30 a.m., half an hour later than I had initially planned. Ah, well, I still should have plenty of time. I donned my new Princeton Tec headlamp. It was only rated at 2 watts but was supposed to be good for an astounding 8 hours. And when I turned it on, I was pleasantly surprised at how bright it was. Well worth the $20.

After using the bathroom facilities 200 feet away from the gift shop, I was on my way. Almost immediately, I got lost, looking for the trail. Two other guys were too. We searched for the trail for about 5 minutes when we finally found it. We started talking, and I learned the other two were from Southern CA.

“First time up here?” one of them asked.

“Yes,” I replied. It turned out to be their first time too, and they seemed to have trained as little as I had for this climb. “Just decided to do it,” the fellow continued. “Probably the wildest thing I’ve tried in my life. My friends back home think I’m crazy to try such a thing since I pretty much just sit at an office desk all day. And you? Especially for going alone?”

“Well, I am sort of known for doing crazy impulsive things, so none of my friends were really surprised. But it still should be challenging, though.”

Just how challenging would it be, I wondered. How would it compare to a century? A double century? A half-marathon? A full marathon?

With these questions in mind, I led the way and was going at a pretty quick, but still relaxed pace. Definitely faster than the 1 mph recommended in Sharon Baker-Salony’s book, How to Climb Mt. Whitney in One Day, but I sensed no fatigue so I didn’t slow down. The other two guys, after 45 minutes, were already tiring, so they dropped back and stopped to rest. That was fine as I had always envisioned doing this hike solo anyhow, just in peace with myself and this monstrous mountain.

The Camps

Arriving at the first campsite, Outpost Camp, just after the sun had broken through the horizon, I noticed that the camp wasn’t much higher than the parking lot and was less than 4 miles into the climb. I wondered why people even bothered to camp out here. Curious, I checked out the solar toilets, only to see a sign saying “please do not urinate in the toilets.” Apparently, the entire system would lock up if it sensed fluids going down. It took me a while to recall that toilets are traditionally used for not only urine but for solid waste, and it’s the latter that these are meant for out here.

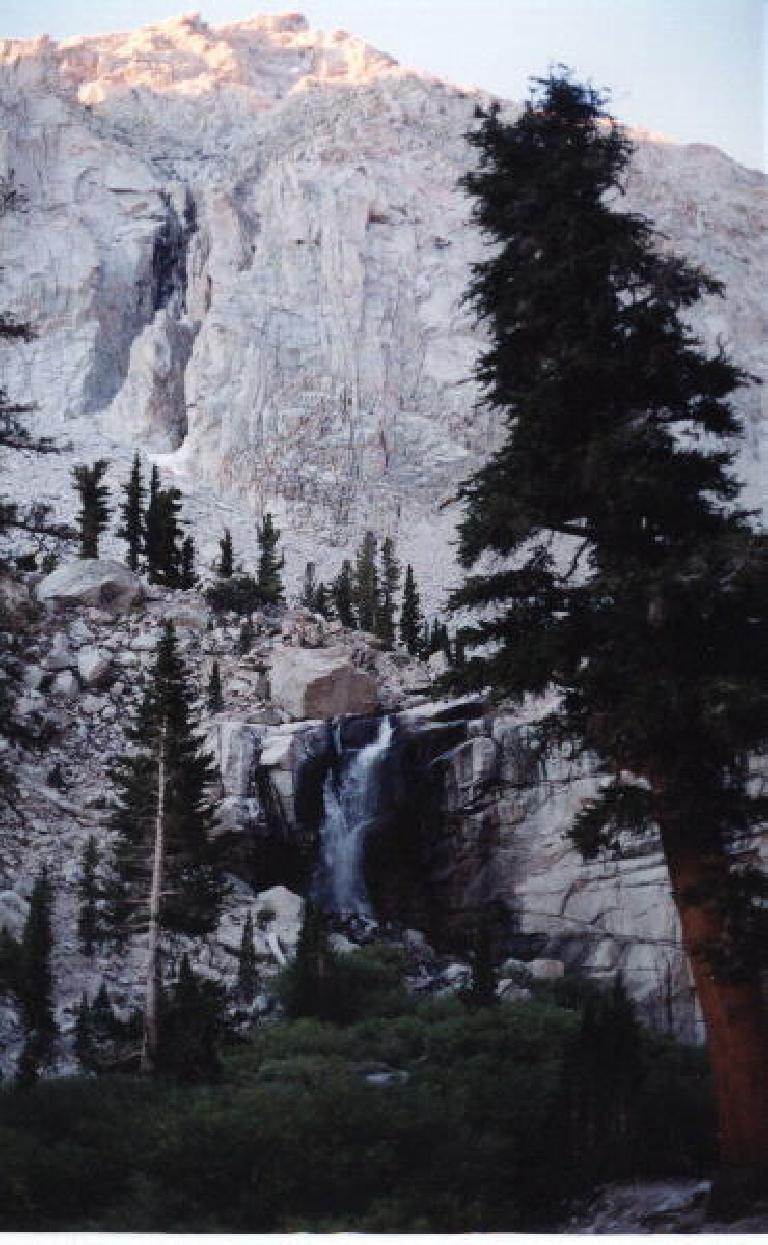

Continuing on, still feeling fine, I took some time to capture the stunning sunrise with my camera. Despite hearing that the scenery on Mt. Whitney wasn’t all that beautiful, I was pleasantly surprised.

Upon reaching the second and last camp, I searched for water. I had read on the internet that this was the last place to get water. However, the article failed to mention that there was no drinkable water available without treatment, and I had mistakenly envisioned there being a water spout like those at Half Dome. It seemed the only water source was the lake near the camp. I had only brought up 72 ounces of water to this point, assuming I could stock up on more water here. Dehydration could become a problem.

Despite this concern, I pushed it to the back of my mind. I was already halfway to the summit and still feeling fine. But here came the 97 switchbacks.

The Switchbacks

“They never seem to end,” I had read in numerous places before arriving at this mountain. It was here when I started encountering a lot of hikers.

One of the hikers was a skinny teenage kid with basically no gear, just a camelback hydration backpack. The storage compartment of his pack was unzipped, and it appeared empty. As he ran past me at the base of the switchback, I couldn’t help but wonder what his rush was all about. For sure, he was not adhering to the 1-mph rule.

It was around this point that I began to feel the onset of a headache. With very little water left, I attempted to force myself to drink. Unfortunately, the water in my new water bladders was starting to taste unpleasant. Their packaging claimed “no plastic smell,” but that was a lie.

Nevertheless, I remained relatively calm, although I could feel myself starting to break a sweat. Ice patches were becoming noticeable on some sections of the trail—enough for maintenance crews to install cables in one area. While my Timberline low-top hikers didn’t offer much comfort and were a bit too large, I refrained from switching to my Nike running shoes, as I had read in the How to Climb Mt. Whitney book that they were unsuitable for the slick surfaces of Whitney. I wished I had brought ski poles for these areas where traction was questionable.

As I approached the top of the switchbacks, I caught up to the teenage hiker. He was explaining to a woman that he had “run up the mountain, but was not feeling so good anymore.” It was a realization moment for me.

In the midst of this conversation, I began to assess my own pace. I was certainly moving faster than recommended, but not excessively so, I thought. With my headache worsening and water running low, I pressed on. And as I reached the Trail Crest, just 2 miles and 700 feet from the top, I felt a surge of determination.

To the Top

The encouragement quickly subsided as my head throbbed. Just two miles, I kept telling myself, a piece of cake. But the reality of the situation started to sink in— two miles meant two hours at the pace I was going.

Soon, it seemed like I could only take 20 or so steps before I’d have to stop to regain my senses. At this altitude, it felt like every step I took was depriving my brain of oxygen until my migraine was so bad I had to stop. A climber on the way down saw me as I stopped, and instantly recognized that I was dehydrated. He offered me some water to fill up.

“I’m not going to need this on the way down,” he generously offered. “Please take all of it.”

I did so and was truly grateful. However, the water tasted as plasticky as the little I had. Forcing myself to gulp it down, I carried on. With every turn, I expected to see the top; it couldn’t be far. But where was it?

Finally, as the trail started to become undefined, I became convinced that the top was just a wee bit further and higher. I was practically bouldering now. My legs were really not all that tired, and at lower altitudes while feeling fresh, I would be going three times as fast. But my head continued to throb, and my footwork was clumsy.

But at last, there was the cabin at the summit just above. I could see and hear some climbers up there. My spirits were up. And ten minutes later, there I was, at the top of the continental United States of America.

On the Way Down

I stayed for only 15 minutes to quickly eat a protein bar and some beef jerky, got my picture taken, and signed the registrar.

“Thanks to Sarah Duvon for inspiring me to do this,” I wrote, almost illegibly. She, a true adventurer, had done this years ago with her mom and sisters over a period of days. While her sisters were suffering tremendously from altitude sickness, she was hauling up everyone’s gear, taking one step at a time. Only now that I had made it to the top carrying far less gear and still having some difficulties could I truly appreciate how difficult that must have been.

Despite going downwards, I really couldn’t seem to go much faster than when I was going up. This was contrary to how I imagined myself practically running down. I guess that despite the lack of preparation, I always imagined myself to be feeling strong and pain-free, bursting with energy—a true high-endurance athlete. I had imagined this to be a literal walk in the park, something much less physically daunting than, say, the Terrible Two Double Century or running my first marathon. But the altitude really got to me—at least my head—despite how capable the rest of my body might have been. Endurance is more than just one’s VO2 Max or physical conditioning; it is at least 50% mental, dependent on morale, patience, motivation, and determination.

Fortunately, despite my headache, I still had ample quantities of the latter, if only because I knew the only way I’d feel better was to get down to lower altitudes as quickly as possible. This still did not stop me from stopping several times. People passed me readily. Going down the switchbacks was especially a demoralizing experience. I could see the bottom very easily, but yet the switchbacks seemed to go on forever. It certainly seemed like it was taking longer to descend than it did to go up them, although in reality this probably was not the case.

At last, I was out of the switchbacks and very close to Trail Camp. I sat on a rock with my head in my arms for minutes. Finally, a group of 3 women and 2 men saw me and inquired if I was okay.

“I’m all right, just have a really bad headache,” I assured them.

“Do you have any Tylenol?” one of the women asked.

“Unfortunately, no,” I replied. She invited me over to the group’s tent to get some.

We then talked for about 10 minutes. I asked where she and her group were from, as I couldn’t quite pinpoint their accents.

“From all over,” the woman, a pretty blonde about my age, replied. Some from Ireland, Norway, Denmark, etc. They worked for Philips in Silicon Valley. “That’s where I’m from,” I replied.

We chatted for a little longer, and under virtually all other circumstances, I would have stuck along longer to get their names, contact info, etc., especially since they were from my area. But my energy reserves were few at this point, and soon I forced myself to carry on while they were going to camp there for the night and save the final push to the top for tomorrow morning.

So after a ranger checked my permit there (permits were strictly enforced, apparently), I made the final descent down. The Tylenol still hadn’t kicked in yet, and still despite being below 11,000 feet now I still didn’t feel any better. I still stopped every 10 minutes or so.

With five miles to go though, I passed by a 45-year-old man named Mike who was resting himself.

“You look like you need some water,” he said, promptly offering some. I gladly took it. We then started walking down together.

Turns out Mike was from Salinas, and had climbed Mt. Whitney practically every year for the last 12 or so years. He always climbed it in one day. In addition to hiking, he played a lot of tennis. He had climbed Shasta a number of times.

It was with his company and his water that I finally started to feel much better. The headache was still there, but it had allayed considerably. With just two miles to go, I took the lead and was picking up the pace. Darkness was setting in but we should be able to make it down just as it gets completely dark, Mike said.

I started seeing car headlamps below, which was extremely encouraging. Another half an hour later, we were down. I shook his hand with thanks and congratulations. We had done it.

So what would be the final impression I took away with me from Whitney? Surely, I’ll be remembering the dehydration and headache I had from Mile 9 on. But equally as much, I’ll remember all the friendly people I met on the climb, people I’ll probably never see again nor got to know past a very superficial level, but ones who embodied not only passion and physical aptitude but also compassion and cheery optimism. Whitney’s altitude can really screw around with your head.

Gear List

I went up wearing two pairs of synthetic socks, cotton boxers, jeans, a cotton T-shirt, Pacific Trails jacket, and Timberland low-ankle shoes. I wore nothing fancy or technical at all, but due to the mild weather conditions, I stayed reasonably warm and comfortable. I would not recommend following this example even though I was lucky and survived. Do not wear cotton on a mountain like this.

| Item | Comments |

| Backpack (as for school) from the Gap | Daypack was large enough for everything, as I did the hike in a day and didn’t need to bring up any overnight camping gear. Many compartments to organize everything. |

| (2) 32-ounce water “bladders” (like Camelbacks) with hydration tube | Ran out of water after 5 hours. Water tasted awful due to plastic taste after that time; basically was undrinkable. Bring more water and/or water treatment supplies (so that you can fill up with untreated water at the camps) |

| 1974 Minolta XE-7 SLR | Given to me by my dad years ago (thanks); takes great pictures. Most of the photos I took on Mt. Whitney was with this. Definitely worth bringing despite its 2-pound weight and bulk. |

| Samsung Impax 210i APS | My “foolproof” camera, with flash, timestamp, and 28-56mm zoom. Can switch between panaramic, wide, and standard frames. |

| Timberland leather shoes | Waterproof, but caused blistering along big toes despite wearing two pairs of socks. |

| Red water resistant Pacific Trails jacket | Trusty but well-worn 7-year-old jacket lined with fleece inside. Nothing fancy, but warm enough. |

| Princeton Tec 2-watt headlamp | Claimed 8 hours of burn time on AA batteries. Just $20 and worked very well. |

| How to Climb Mt. Whitney in One Day by Sharon Baker-Salony | Essential book that doesn’t take much space in pack at all. Consulted it several times for altitude/distance and “where am I” questions. |

| Pearl Izumi lobster gloves | Water resistant and warm, if dorky looking |

| Kleenex | Essential |

| Baby wipes | Not essential but nice |

| Compass | Came in handy a couple of times |

| Running shoes | Did not use, but probably could have until the switchbacks where there was some ice. In fact, I should have switched over to them when my feet started to blister due to the hard, ill-fitting Timberlands… |

| Shorts | Did not use |

| Bug spray | Did not use |

| Bandages/first aid | Did not use |

| Trader Joe’s food bars | Yummy with a 40/30/30 mix of carbohydrates, protein, and fat |

| Promax protein bars | Filling with lots of carbohydrates and protein |

| Raisin nut bars | My only bread product; helped hold water down as they acted like a sponge |

| Trail mix | Tasted okay on the trail |

| Beef jerky | Strong odor and require a lot of chewing. Probably contributed to dehydration; disgusting after eating it for awhile. |

Things I Wish I Brought Along

| Item | Comments |

| More water | Dehydration was a big problem for me, inducing altitude sickness and a big headache. Headache would not significantly subside until I was five miles from the finish and a 45-year-old hiker I met on the trail gave me some water (thanks, Mike). Iodine/filter/etc. would have been essential for untreated water that was available on the mountain. |

| Sandwiches and other “real” food | My food bars, trail mix and beef jerky was NOT particularly appetizing and I basically had to force-feed myself. |

| Ski poles or walking sticks | My legs were not very tired, but ski poles would have allowed me to descend with more confidence and more quickly as they aid with traction. |

![Outpost Camp: "Do not urinate in the [solar] toilets" (!) sign](https://felixwong.com/gallery/thumbs/m/mt_whitney05.jpg)

There are 5 comments.

Thanks for the detailed description of your climb. I really enjoyed reading it. The most climbing I've done was a number of years ago in Big Bend, TX....the South Rim. My son, Spencer Bailey, was in school at Alpine, Tx.at the time and wanted me to do this. I'm glad I did.....it was a memorable occasion for me

Hi Felix,

I first stumbled upon your site researching to do the Whitney one day hike. There was a lot of valuable information about your hike, that helped me, never having done anything like this before. Thanks to sites written by people like you, I did the Whitney hike in less than 12 hours and it went off without a hitch. I'm now doing the biking deal too, thinking about the Mt Tam Century, but moreso, the Death Valley Century in October. Have you done that, or have any info about what its really like?

thanks for a great site...its so valuable for the rest of us.

Barb

FELIX,

AWESOME READ! I WENT TO MAMMOTH FOR NEW YEARS AND ON THE WAY HOME I LOOKED OVER AT MT. WHITNEY AND SAID I'M GOING TO CLIMB THAT. SO HERE I I'M AT YOUR SITE, AND LEARNED A LOT OF HELPFUL INFO.

THANKS FOR THE HELP,

TIM

Great blog post! Congrats on the hike.

Regarding your comment: " What the heck is this punk doing running up the mountain like that, I wonder. Certainly not following the 1-mph rule!"

I just wanted to quickly point out that some people do train to "run" Mt. Whitney. In fact, that's what I'm training for right now. I'm a dedicated trail runner who's always dreamed of running up Whitney, although I'm sure it'll be more of a "run & power walk" type of ascent, but it'll be quick, and with minimal gear.

I'm currently in the lottery for a permit (I've asked for any two days in the month of September '09) and with any luck will be jogging past hikers on the trail later on this year :-)

I completed this climb in 1984 when i was 20 years old. I sometimes think about returning - 20 yrs - 25 yrs later etc. Actually I am in better shape now - i was a tubby fat kid then. What i remember from that day was standing on the summit and signing the book . I made it alone with no help from anyone. Then the trip back. What a pounding the trail does on your feet knees and hips. I limped back to the Portal. Then I bought a package of fig newtons at the store and devoured them.......