Café Ruiz Coffee Tour

I’ll be honest—one month ago, I really had no idea that high-quality coffee came from the mountains of Panama. Nor did I really care. I drink about three cups of coffee a year, and that includes caramel frappuccinos that is more like a desert than a drink. When I go into a coffee shop I order something like a Moroccan Mint or English tea. Even on the rare occasion I’m in a Starbucks (mainly to use their free wi-fi in, say, Mountain View, for example), I’d order a shaken iced green tea, size tall (small).

I sort of entered a whole new world, then, shortly after meeting up with Tori down in Boquete, which apparently is to coffee as Bordeaux is to wine. If Tori—a true coffee aficionado—hadn’t already made it perfectly clear that the world’s best coffee came from this region, then Carlos—Café Ruiz‘s most excellent tour guide who we met through Habla Ya—did in no uncertain terms.

“Café Ruiz won the international award for the world’s best coffee three out of the last six years: 2000, 2002, and 2004,” he explained. “The other three years, a rival company here in Boquete won.”

“Everyone here is extremely proud that such a small town can produce the greatest coffee in the world,” he added.

Carlos’ enthusiasm was infectious. Here was a guy who clearly knew his coffee (before he was Café Ruiz’s tour guide, he was a professional coffee taster), not only about how a good coffee tastes like but exactly how to make good coffee.

Not that he was a complete coffee addict. “I actually don’t drink that much coffee anymore,” he claimed. “Usually only four cups a day.”

Only four cups a day! I struggled to suppress a laugh as I tried to imagine how many cups a less ascetic Boquete resident drank. Six? Ten? Finally, Tori said to Carlos, “That’s about how many cups Felix drinks in a year,” to which Carlos just sat pensively, perhaps thinking about how deprived I have been.

Indeed, I did get a new appreciation for what making good coffee entails. Prior to the tour, I thought that coffee beans are simply grown, picked, and bagged before being thrown into a coffee maker by Mr. or Mrs. Sleepyhead to magically create some bitter-tasting but great-smelling black liquid. It turns out this is not the case.

In fact, producing good coffee is more complicated than making Barefoot Contessa’s meatloaf. To begin with, the right conditions need to be present just to get a coffee plant to grow. Boquete, with its temperate—yet rainy (during Wet Season)—climate and volcanic soil has them. If you go up just a little higher—say, nearby Cerro Punto—coffee beans will not sprout.

Coffee trees need to be strategically planted. At Café Ruiz, coffee trees are grown in between fruit trees, which are occasionally pruned to provide the right amount of shade. The fruits also attract birds which also eat insects. This way, no chemical pesticides need to be used.

After the coffee beans are grown and turn red (after being green) when they are ripe, Café Ruiz employs 14 steps in the processing of them, including:

- Hand picking the beans, being sure to twist them off of their stems so that the coffee tree is preserved and lives longer.

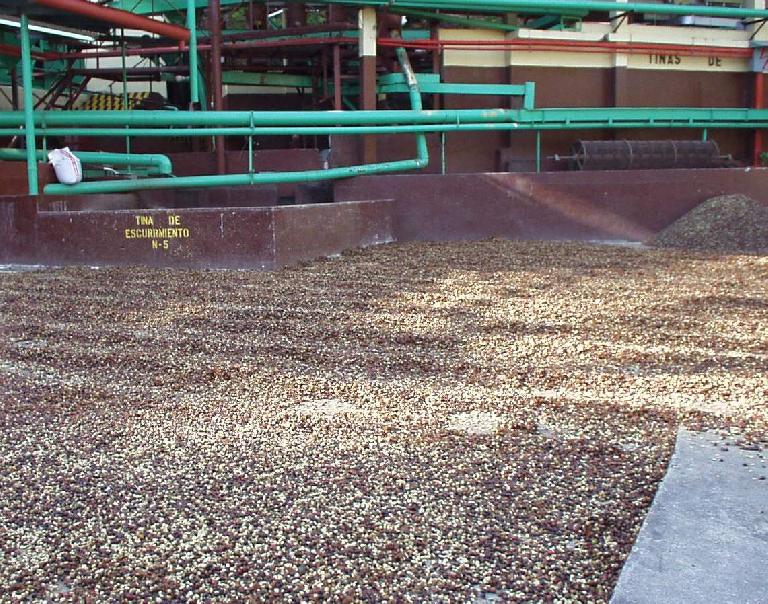

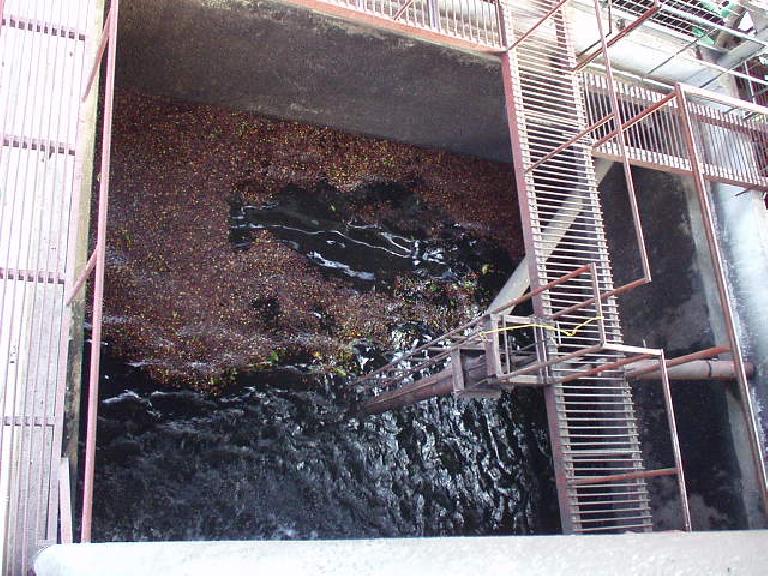

- Separating out the less-dense beans (which often are less dense due to insects eating the insides of them) from the denser ones. This is done in a huge vat of water; the less-desirable beans do not sink and hence are called “floaters”.

- Squeezing the beans (like squeezing peas out of a pod) to get two beans. This is done by a machine.

- Fermenting.

- Washing.

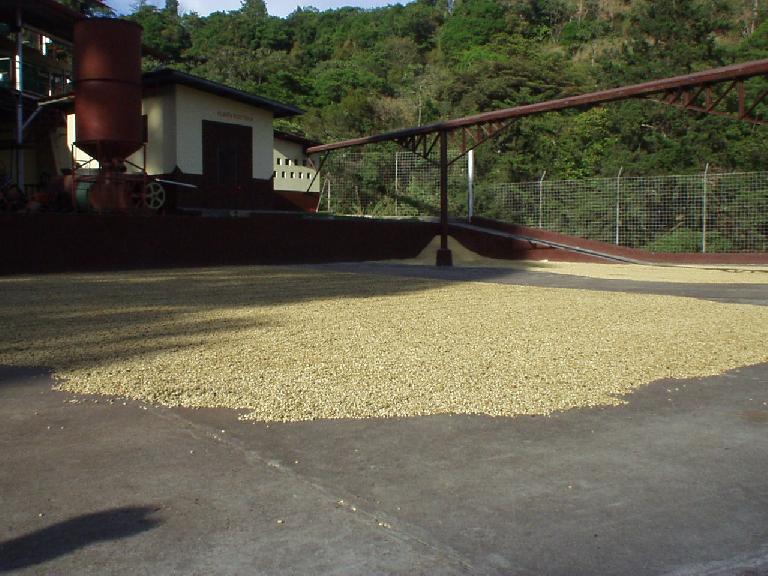

- Pre-drying.

- Sun- or oven-drying. Surprisingly, sun-drying yields no advantages (including taste) over oven-drying other than using less energy. In fact, it takes longer to sun dry. The fuel used to oven dry the beans are the beans’ own skins (see step 9).

- Aging of the beans inside the bags for precisely four months.

- Remove skins.

- Separate by size.

- Separate by density.

- Separate by shape.

- Separate by color (this is more of a final quality assurance step.)

(Hmmm, I seem to be missing one step in here. Perhaps Tori or someone can tell me what it is.)

After the 14 processing steps, the coffee beans are sold and shipped, and then roasted by the receiving companies. Café Ruiz also has a roasting plant for their own coffee shops, but because we had a special afternoon tour just for us, the roasting plant was closed so we could not visit it.

In the midst of the coffee tour, Carlos offered his judgments on coffee brands sold in the U.S. and the world.

“Starbucks is for people who like coffee. Peet’s Coffee (which started up in Berkeley in 1966 before Starbucks) is for people who LOVE coffee,” he stated. Café Ruiz apparently sells some beans to both companies.

“Much of the coffee beans that Folgers use are floaters. So we call Folgers, Floaters. Same goes with Nestle’s Nescafé. Nescafé is No Es Café,” Carlos said with a wide smile.

“The good thing about floaters is they have a little more protein,” he added. Then after pausing: “From the insects inside them, you see.”

Ok! While that did not inspire me to drink any more low-end coffee than I already do (don’t), a quick trip to a local Café Ruiz coffee shop to try a delectable cup of cappuccino convinced me that good coffee is something that even I can appreciate. I wouldn’t bet that I’ll be drinking four cups of coffee a day any time in the future, though. After all, I gotta save some for the true coffee aficionados, even those Boquete residents who claim “not to drink too much anymore.”

There are 3 comments.

Great article!

Makes me want to run over to Peet's :-)

Which was actually founded in 1966 in Berkeley.

But I can see that a Stanford alumn can give the credit across the bay ;-)

Thanks for the correction! I'll revise the article...

This tour was amazing. We also had Carlos as a guide; he was incredibly knowledgeable and entertaining. The success of any tour is dependent on the guide and Carlos is the best. I learned a lot about coffee and have a much better appreciation for it. We brought home many packs of Ruiz coffee and I still want more! I definitely recommend this tour.

I didn't post as many pictures as you, but I have a few here: http://www.gennykothari.com/blog/2011/10/23/panama/ (It's a Chlidren's Photography blog normally, but it's a good home for the pictures). The main site is http://www.gennykothari.com/

- Genny