Frank Shorter Presentation

Even though his fame came before I was born, I was familiar with whom Frank Shorter was from the movies Prefontaine and Without Limits and Kenny Moore’s book Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. From Wikipedia I also knew that he was a Yale grad and had attended law school at the University of Florida. But what I did not know was that this living running legend lived in Boulder, Colorado, only 55 miles south of where I reside. For the last 40 years, in fact.

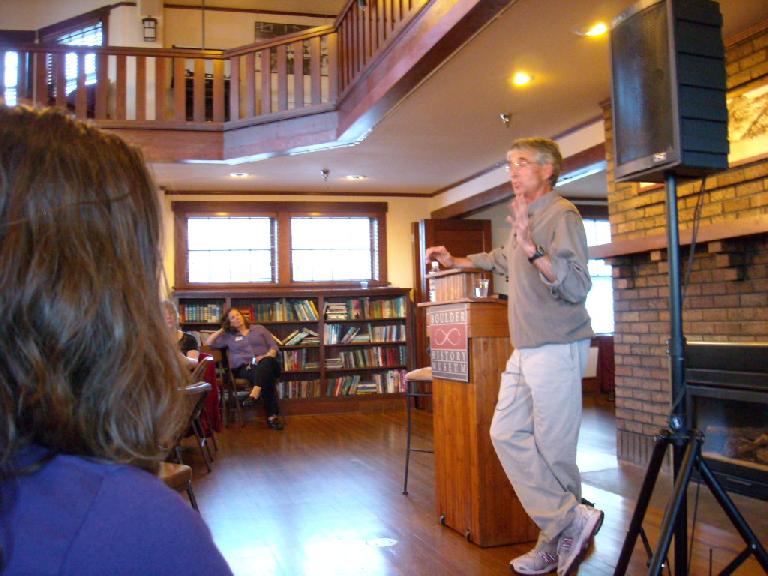

“I find that I am most productive in a place that suits me best,” he said at a presentation in the Chautauqua Center. Funny, that’s exactly why I had moved to the Front Range.

It turned out that Frank’s search for his ideal place to live was a little less comprehensive than mine, but in the end it turned out just fine. After a brief stint in medical school in the late 60s, he became focused on training for the Olympics and Boulder was the only city in the United States located above 5,000 feet with an indoor track. After living in Boulder for some time, he also realized that the climate was perfect for training year-round, having 300 days of sunshine each year. Later he convinced several triathletes such as Mark Allen and Kenny Souza to move to Boulder to train for its climate and culture. He is largely responsible for why Boulder has become a haven for the elite athletes it has today.

He cited other factors: a unique relationship between the University of Colorado and the city, and personal connections that helped promote his training, love of running, and future business success. He loved living there so much that even though as a poor, amateur athlete in the 70s, he was determined to “make it work.” He was “going to do what I needed to do in order to be in a place that could provide what I needed.”

An example of this is how he made a living while he was still competing. Before the 80s, the AAU had draconian rules which virtually ensured they lived in poverty in order to retain their amateur status, not only disallowing product endorsements but also, say, coaching tiny-tot soccer. Armed with a law degree, managed to convince the AAU to allow him to open up his own clothing store that sold superior running clothing he designed. His retail store not only provided him with living wages, but offered jobs to other athletes who needed flexible work schedules to train.

Years later his law degree came in handy again when he found a loophole in the AAU’s rules that allowed him to help set up trust funds for top athletes. This allowed amateur athletes to compete for money that would go into the trust funds to provide themselves with money to live off of.

In the early part of the new millenium—shortly after a major drug scandal in the Tour de France—he was nominated to be the chairman of the United States Anti-Doping Agency. Hence, as one of the nation’s foremost experts on the matter, it was interesting to hear him speak about the state of drug use in sports. Without making specific allegations against certain individuals, he implied that doping is still rampant in sports especially in third world countries that lacked oversight, and that it is not limited to aerboic sports such as track and field, swimming and cycling. It is highly probable that many professional football, basketball and baseball players use drugs such as human growth hormone and steroids too, especially since (in the words of a professional baseball player) “they work too well.”

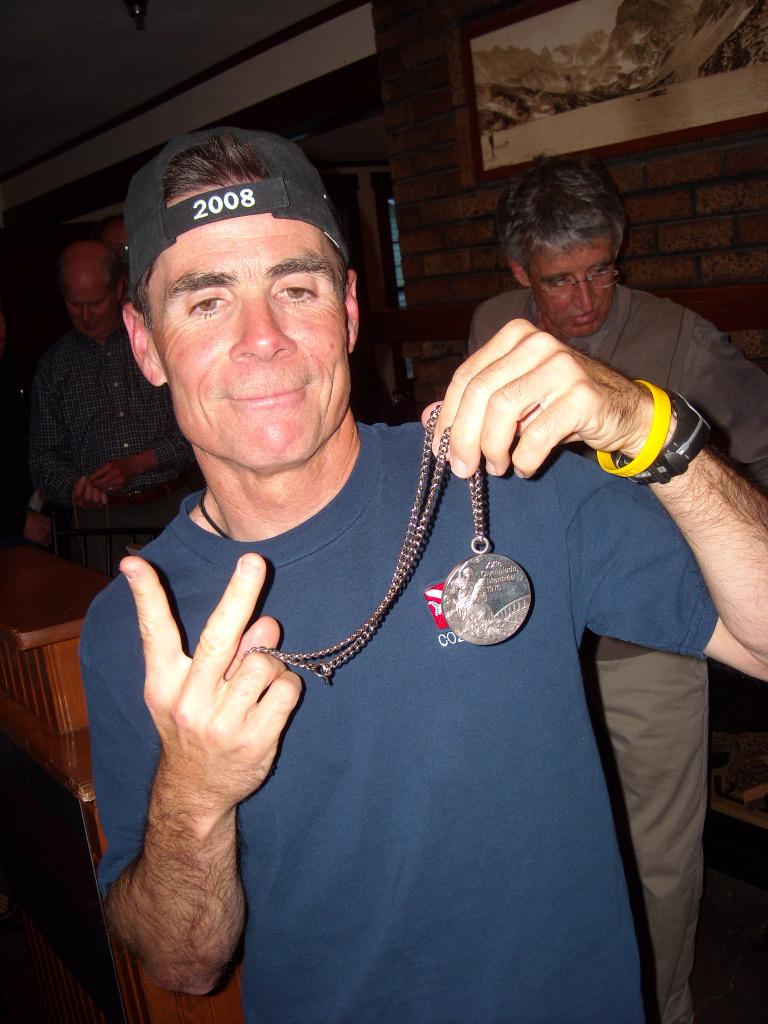

Although he was probably too modest to admit it, perhaps Frank’s greatest contribution to the sport was the millions of people he inspired to run after winning the gold medal in the 1972 Olympic Marathon, followed by winning the silver medal in the same event in 1976. At the time, running was still enough of a fringe sport that if a person was out running on the street, passerbys would wonder if he was being chased. Frank’s high-profile victories got Americans off the couch and into the 70s phenomenon known as “jogging.” He also was one of the founders of America’s largest 10k race, the Boulder Bolder.

At the end of the talk, Frank busted out his gold and silver medals which Eddie, Raquel and I enthusiastically grasped and posed with for our cameras. It was a real treat to be able to hold genuine Olympic medals, especially those awarded to an American legend of a sport that we love.