Eastern Sierra Double Century

It was the middle of June when I had a change of heart. Back in May, during the Davis Double, I decided that six double centuries in two years was enough and that I didn’t mind not completing the California Triple Crown despite already having completed two out of the three required rides. Half of my doubles were not the most fun, even painful, and I decided I am not a masochist, contrary to what my friends thought.

But time has a way of retaining good memories and erasing the bad, and there was another factor, too. In the intervening weeks between the Davis Double and my friends’ June graduation at Stanford, I was picking up bad habits including drinking more (socially), swearing more, accomplishing less, etc. Eventually I decided it was time to get back on track and return to a more life uplifted by the simplest of all joys, like spending time with Mother Nature and exploring the vast expanses of Earth.

So all of a sudden I was anxious to complete the goal I had set at the beginning of the year. And this time I was determined to have fun, doing a ride that would avoid the struggles of 100 degree heat, extreme cold or rain, and ridiculously steep climbs.

Since the top-rated double century of the California Triple Crown was the Eastern Sierra Double, I picked that one.

The Drive

The start of the ride was in Bishop, CA, 60 miles southeast of Yosemite and not far away from the Nevada border. It was also 280 miles away from Fremont, my current residence, and hence I planned on driving for 5-6 hours.

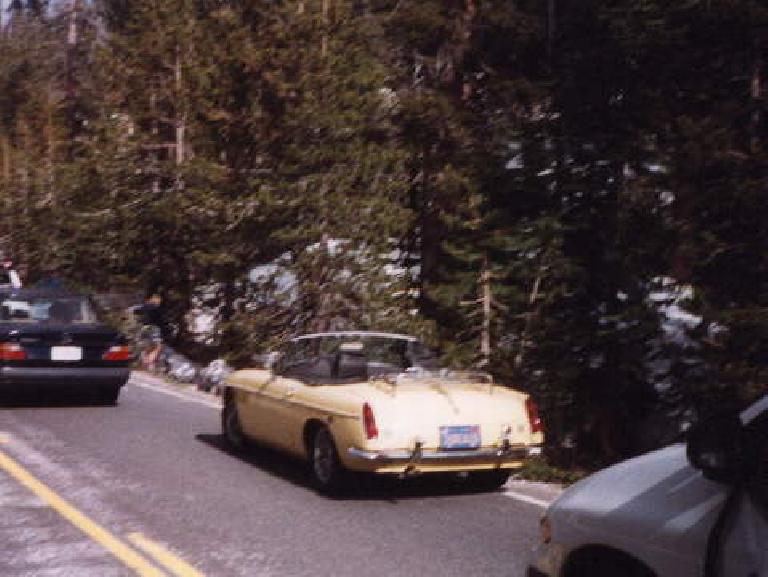

That was a poor estimate. I left on the Friday before the 4th of July, and it seemed like everyone was leaving for vacation early too. Traffic from Fremont to Manteca was stop and go, and there was the heat to deal with. Luckily I had fixed a small cooling system leak and topped off the radiator of my 1969 MGB beforehand, so she was handling the temperatures soon.

The drive through Yosemite was spectacular, with lots of curvy roads through some of the most gorgeous scenery on the planet. It was a great day for a British sports car.

But then midway up Highway 120, traffic came to a standstill. People were getting out of their cars. The road was temporarily closed to clear an accident, and would not reopen for hours. The road, then, had literally turned into a parking lot! Hmmm, what to do…

The answer was perched on top of the MGB’s luggage rack, in the name of Canny, my race bike. What better way to loosen up my legs for tomorrow’s ride by doing a little bit of riding in Yosemite? I also was curious as to what was going on in the front, so in a matter of minutes, I had my cycling shoes on and my bicycle off of my car.

People laughed as I climbed onto my steed. I guess it was pretty funny to watch a guy ditch his car and hop onto his bike because of backlogged traffic.

“Hey, I always to go biking in Yosemite, and here’s my chance!” I told them. Off I went.

At the blockade, there was a helicopter in the middle of the road. Someone was trapped in a car and first responders were trying to get him out. I couldn’t see the actual scene of the accident, but it was probably best I didn’t. I hate blood and gore.

So I headed back down and took on the role of a messenger. Everyone wanted to know what I saw! So I went up and down the line of cars, returning with updates on the situation and talking with a hundred people in the process.

It was interesting to see how others passed the time. Despite the inconvenience caused by this unfortunate incident, most people were determined to have fun. Some people went for a short hike up the snow-covered hills. Others were sliding down the hills. Others practiced their golf stroke!

But thankfully, the helicopter finally took off, and we only had to wait for another ambulance and a tow truck. After those came, I returned to the car and put put Canny back on top. Two hours after we stopped, we finally got going again.

The drive continued to be very pretty until we hit Highway 395 and headed south. This would be the area the Eastern Sierra Double would go through. It was nice, but not as gorgeous as Yosemite. It was also really warm outside by the time I got to Bishop, at 8:30 p.m. or so. I was sweating in the car. I wondered: is this going to be as hot as the Davis Double two months ago?

The Ride

Miles 0-25

I got a good night’s sleep at a really cheap motel before biking over from the motel to the Tri County fairgrounds. From there, police cars would escort the cyclists out of Bishop for the start of the ride. I was almost there when I saw a bunch of riders with a police car following. So I was almost on time—maybe one minute late.

The air was cool and I felt good. Mountains abound on the east and west sides of us, and for the first 20 miles, we were yo-yoing between them. The ride was supposed to have 10,000 ft of climbing, but the first 20 miles seemed flat to me. Later, another cyclist told me that we climbed at least 1,200 ft during that part of the ride, so it must have been a gradual ascent.

I was definitely feeling better than at the Davis Double six weeks ago. Up to that point, the ride was pretty and I felt relaxed and at peace. This is what cycling is supposed to be like, I thought. I was also determined to have fun this time around.

So at the first checkpoint I took my time and chatted with other cyclists. One guy, named Milo, noticed my Stanford jersey and told me he’s working in the physics department at the Stanford Linear Accelerator. We talked for quite a bit and decided to ride together. I thought it could be nice to have some company, especially with someone from where I came from.

Mile 25-110

We talked about the rides we have done and our goals for the ride. He had done two doubles and was hoping to get back before dark. I thought that would be a stretch, but I was aiming for that too.

Milo loved to talk, especially about all the bicycling research he had done. He was also collecting more data than I was. For example, we both had cycle computers with speed and cadence, but he was also using a heart rate monitor. (My transmitter hadn’t been reliable, and hence I left it in the car.)

He also had an altimeter. This was a great thing to have considering the altitude we rode at—between 6-9,000 feet—and the climbing we would do.

“I’m in physics,” Milo said, “I need information.”

One thing I didn’t like was the amount of he cussed and how he seemed to be belittling other riders who were passing us up. He said they would blow up and be hating life later. I thought otherwise—a lot of these folks looked really fit.

But I stuck with Milo’s slower pace. I already set a personal time record for myself earlier this year at Solvang and today was just going to relax and enjoy the beautiful surroundings.

We stopped every 20 minutes to dismount and stretch. “My coach in Colorado emphasized the need to stop and stretch,” Milo said. Whatever, I thought. In fact, I was feeling very fresh due to all of the stopping, so went along with it despite preferring to keep on riding.

My spirits picked up when we went through a city with a Fourth of July parade.

“Other people are home celebrating their 4th of July with a barbecue, and here we are doing something insane like a 200 mile bike ride,” Milo said. I told him this was a great way to celebrate one’s independence. It also offered freedom away from a frenetic, electronic world. It was simplicity at its finest, passing the miles along the way.

But then we climbed above 8000 feet and Milo complained of altitude sickness, headache and stomach ache. I recalled that the night before I had a headache too for most of the night. But Milo was the type of guy who made sure you knew about his pain by constantly complaining. My sympathy turned into annoyance. Pervasive negativity has that effect on me.

We stopped yet more frequently. Besides the checkpoints at miles 48 and 75, we even stopped at a gas station for a long time. Milo told me that the cashier was familiar with the route and that we’ve done most of the climbing already. He wasn’t feeling well though. Afterwards, when we started riding again, he wanted to take a stretch break every 10 minutes.

He started climbing slower and complaining more. I started getting really annoyed with both his whining and also things like taking a leak right on the shoulder of the road instead of discretely going to a faraway bush or tree.

The grossest part came later, though.

“My stomach is really killing me,” he state at Mile 80. “Do you think I should throw up?”

At first I thought he was joking. When I realized he wasn’t, I flatly told him “NO!”

But half an hour later we stopped on the side of the road. He then put his finger down his throat to empty out the contents of his stomach. I stayed 50 feet away with my back towards him but could totally hear him. Barf!

I was so disgusted. Why the heck did I agree to ride with this guy?

We also lost a lot of time. I calculated that at this pace, getting back by midnight would even be a stretch. Most of the other cyclists were long gone. Yet Milo cluelessly insisted that there were still many behind us.

Finally, at Mile 90 and after another one of his barfing routines, I had enough. I had to leave him.

“Are you feeling okay enough to get to lunch alone,” I asked. His reaction surprised me.

“No, please don’t go, I need you to ride with me.” He pleaded enough that I promised him to with him until lunch. But I also told him that I might ditch him after that.

We rode quietly after that. To his credit, he also tried to pick up the the pace.

When we got to lunch, it was 4:30 p.m. The volunteers were closing up the rest stop. Out of 270 starters, we were the last ones there except for maybe one or two other. We had gone 110 miles and spent more than 11 hours on the road. It was my slowest century, even surpassing the time of my very first century I did on a borrowed bike.

I did a quick calculation and realized that at this pace, we’d be lucky to get back by two or three o’clock in the morning. But it was his personality that clinched the decision on whether to stay with him or not.

Mile 110-183

After the lunch stop, I decided to pick up the pace. If he could keep up, fine. I thought that was unlikely though. Heck, even if he was feeling 100% well, I wasn’t sure his 46-year-old body would be able to match my 23-year-old one.

In fact, after checking in with the timekeeper at the lunch stop, I let Milo have a five-minute head start. Yet it took only 10 minutes to catch up to him. We rode together for another 10 minutes. There was a little bit of hill climbing ahead for the next few miles.

“We’re going a good pace, huh?” Milo said.

I didn’t bother to reply. The truth was, I hardly needed to breathe at that pace.

He worked on persuading me to stay. “I was just thinking… we aren’t going to get to that checkpoint [at mile 163], where I can pick up my lights, before dark,” he said. “But you’re going to be picking up your lights at the next checkpoint [at mile 135], right?”

I started wording things carefully, as I knew what he was getting at: that he wanted me to stay with him because he wouldn’t have lights. “Yes, but we won’t really be needing our lights too much… I’ve done a few night rides without them.”

“I ain’t gonna get killed on some highway at night, though. My wife, at just 36 years of age, got killed in a car accident and I am my kids’ only parents. I’m not going to get killed, ya ‘know?”

He continued on and on. I felt sorry for him, but was really annoyed. I felt he was trying to manipulate me through guilt to ride with him. We came to this ride independently and I didn’t want to be responsible for making sure he got back to the finish safely. He already annoyed the heck out of me with his crudeness and inconsideration. I had enough.

So as we climbed up the hill, I shifted up a gear or two. Then another. Then another. I was feeling strong and it was pretty easy to get a gap on him.

Within a minute he was 100 feet back already. After cresting the hill, I turned my head around and held up my hand to wave goodbye. Goodbye Milo… and good luck.

After getting into a full aero tuck, I pondered what had just transpired. A debate went in my head that went like this:

Voice #1: “You just abandoned a fellow cyclist in pursuit of finishing at a reasonable hour.”

Voice #2: “I stayed with him for as long as I could tolerate and longer than promised. I am not going to get to the finish at 2-3:00 in the morning and not get ride credit. I have invested a lot of time, dollars, and energy in the pursuit of the California Triple Crown, and the pace we were going wasn’t going to cut it. Besides, he said he was feeling okay, and yet was pondering the issue of quitting. And if he does quit, what would have been the point of staying with him? I’d get to the finish so late that the organizers will have left already.

“We came here independently and there was no contract between us. We were not friends; in fact, I thought he was a jerk. If he were a friend, things would have been different.”

Having made the decision, it was time now to truly ride. The roads were downhill and I was maintaining a steady 30+mph. I was bent over the handlebars and it was like I was doing a time trial.

Accordingly, the next rest stop came quickly: 1h15m for 25 miles, or a 20 mph average despite the slower miles with Milo right after lunch. I probably averaged 22-23 mph in the last hour or so. At least, the speed on the speedometer read 25-40 mph most of the time.

One of the guys eating at the next rest stop would corroborate on how fast I was going. “Wow, I saw you on your way to lunch, and that was when I had just left. You must have been cooking!”

“I was,” I confirmed. Encouraged that was now not the last bicyclist on the course (but still probably the last one who was determined to finish all 200 miles), I spent nearly 15 minutes at that checkpoint before putting on the hammer again.

It was 6:45 when I left. The next stage took off with a furious downhill. A female rider had left the checkpoint two minutes ahead of me, but I quickly caught up and passed in a full aero tuck, hands right next to the stem, chin practically on the stem, and elbows hugging the ribcage. My downhill skills—at least on straightaways—had always been ok, being able to get narrower and lower than most riders. Today was no exception.

Down the hill the cycle computer read 51.5 mph! I sustained this for 30 seconds maintained speeds over 40 mph for minutes. I laughed at a 30 mph recommended speed sign in a corner as with my little race bike, I could safely do 10 mph over this with this downhill.

I hit 52 mph on another occasion, which was a new speed record for me. The roads were optimal: smooth and wide, with great visibility and absolutely no cars. I’ve never felt so relaxed and confident at these speeds.

I got to the next rest stop at mile 165 at 8:10 p.m. That’s 30 miles in 1h25m. I felt relieved knowing that I had only 35 miles to go and the sun was still up, if barely. I chatted with one of the volunteers at the checkpoint while she served some delicious Campbell’s Homestyle chicken soup.

Before leaving, I asked, “Just 18 miles to the next rest stop, right?” The hostess replied, “Actually, Hugh was saying it’s just 11, and another guy was saying just 12.”

Great. Time for another time trial!

Miles 165 to the Finish

Hammering again, I could see the blinking rear lights of a cyclist half a mile ahead. But the winds picked up and I struggled to maintain 17 mph. The terrain also seemed to gradually go up. Thinking that the rest stop was just miles away, I kept up the intensity.

I checked the cyclometer every few minutes. Miles since the last checkpoint: 10 miles, 11 miles, 12, 13. Where’s that rest stop? It turned out the route sheet was correct—it was after 18.

The winds picked up even more. I was tiring but kept up the pace. One nice distraction was a rather awesome display of fireworks, probably 30 miles ahead. In this part of the world, with smog-less air and no buildings and tall trees, one could see these things.

At last, I got to the rest stop at mile 183. It was 9:35 p.m. “There he is!” exclaimed the cheery hostess with a British accent. We first met at the second rest stop, when I was still riding with Milo.

“You’re going to make it, just 15 miles to go,” she said. She handed me a Mountain Dew. It tasted so good especially compared to the 15 or so water bottles I had drank earlier. Three other riders were there.

“When are you planning on closing up?” I inquired.

“Soon,” she replied. So despite my herculean effort, I had made it to the last rest stop before it closed without much time to spare. I felt somewhat vindicated for ditching Milo.

“There shouldn’t be any other riders on the course,” she continued.

One of the others interjected, “Some riders were just coming into lunch at 4:30.” I laughed because one of those riders included myself.

“Well, if they were just coming into lunch at 4:30,” she said, “they’re not going to make it.” I laughed again and told them my story.

Finally, at 9:50, the three other riders and I took off together. Two of the people are a married couple and they lead the way. Determined to help the others out, perhaps due to some residual guilt for abandoning Milo, I waited for the fourth person (a lady in her 40s) several times to tow her back up to the others.

At one point she inquired, “Is that a fire ahead?”

The fireworks ahead had been replaced by a conflagration. It was out of control.

What a disastrous way to end a Fourth of July. Firetrucks and police cars were soon passing us. At Mile 190, we were enveloped by smoke carried by the strong headwinds of the last 30 miles.

We watched the fire all the way to the finish of the double century. We seemed to be riding straight towards it.

But finally we turned away from it and instead saw the lights of Bishop, a city booming with restaurants and motels, in an otherwise totally deserted part of the world. It was good to be back. We made it!

The End

I rolled into the finish a little before 11:00, just as I told Milo I wanted to do. I inquired about Milo, but the guy at registration told me that if he didn’t come in before me, he wouldn’t know about it. I assumed he was sagged in.

The British lady from the previous rest stop was here.”You made it!” she exclaimed.

Indeed, I completed the California Triple Crown, even if it took a herculean effort this time. I looked back at the day’s events with some wonder: 110 miles in 11.5 hours, and the last 90 miles in under 6, including time spent at rest stops.

But that was not what I was thinking about at the time. I was thinking about the fellow cyclist I had abandoned, and the massive conflagration at the end. It was a reminder that as I focus on my own goals, there are others struggling and dealing with their own problems. I had done this ride to temporarily “get away” from the “real world,” and yet the real world had come back to me.

Ride Data

- 198 mi.

- 5:20 start, 22:50 finish = 17.5 hours

- First 110 miles: 11.5 hours

- Last 90 miles: 6 hours

- Average Speed: 14.0 mph moving, 11.3 mph overall

- Max Speed: 52 mph, on two occasions

- Total Climbing: 10,000 ft

Rating

(5=best)

- Scenery:4

- Support/Organization: 2

- Food: 3

- Weather: 4. Would have got a 5 were it not for the headwinds at the end.

- Relative Difficulty: 3

- Overall Rating: 3