Sierra Road, San Jose, CA

Today was Stage 2 of the inaugural Tour of California, purportedly the most difficult stage of the 7-day bicycle race. Why? Two words: Sierra Road.

“The stage wasn’t too hard until the climb,” elite bicycle racer George Hincapie was quoted as saying in an Associated Press article. “But Sierra Road (a nine-mile climb) was definitely hard. I didn’t know the hill, but it might have helped to know the climb a bit. It was a really tough, steep climb. It was never-ending.”

I could only smile as I revisited my own memories of the climb from bygone years.

First Encounter

My first experience with Sierra was on a winter day in late 1998 with my friend, David Hung, while I was still living in Fremont, California, less than 20 miles away from the climb.

On this particular day, it was forecast to rain cats and dogs. For some inexplicable reason, Dave and I therefore thought it would be a terrific day to go for a ride.

Dave led the way as southern Milpitas may as well have been Myanmar as far as my knowledge of its streets was concerned. We went up Calaveras Rd. and then headed towards Sierra, which one of Dave’s coworkers had described to him as “a pretty awesome climb.” Our plan was to ride down it, then turn around, climb up it, and head home.

We did the first part all right if you consider “hanging onto dear life with a death grip on the brakes, skin soaked to the bone and teeth uncontrollably chattering” as riding. During the descent—whose steepness and hairpin turns startled me—we hit speeds in the upper 30s while our brake pads struggled to firmly mate with the rims amidst a mixture of rainwater and aluminum oxide sloshing about the wheels. I believe my brake pads lost about a third of their thickness on that day.

When we got to the bottom, the two of us—almost as cold as icicles—did the manly thing to do, which was to retreat to nearest donut shop and warm up. As Dave recalled seven years later:

I remember only having enough money to buy a coffee at the donut shop, and holding it to try and stop from shivering. My teeth were definitely uncontrollably chattering! I even stood in front of the hand drier in the bathroom for a few minutes to try to warm up, but with little success.

After our jaws dethawed and we could actually utter an English word or two again, it didn’t take long to make a decision: take the quickest, shortest way back home via Piedmont. The Sierra climb would have to wait another day.

Encounter #2

My second encounter with Sierra Road actually wasn’t on my bicycle, but actually in a car.

The MG Owners Club was doing a driving tour of the East Bay, and in a tight “paceline” formation, our peloton of MGs attacked Sierra Rd. with the alacrity of Michael Schumacher driving onto a Formula 1 course.

The good news is our 20-50 year old British sports cars successfully powered up the climb and around the corners, sometimes with squealing tires, but always firmly in control. The bad news is, in doing so, we nearly scared the living daylights out of some of us.

Remarked the late Earl Pierce, who had been a pilot some time earlier in his 60+ years of life and took to the climb in his red MGB roadster, “That was the first time I ever got acrophobia in a car!”

Indeed, Sierra Rd. is not just steep; it has a number of switchbacks abutted by sheer dropoffs and no shoulder. I recall a couple of years later when I was hanging out with my friend Sarah DuVon—who was on a Search & Rescue team at the time—and she was called into duty because a car had rolled off one of these cliffs.

Apparently, if you’re not careful, Sierra Road will get you one way or another.

The Most Lasting Memory

And finally, about my first time going up Sierra Rd. on a bicycle.

It was the year that I was trying to become the youngest rider to complete the California Triple Crown Stage Race up to that point. This stage race involved doing the three most masochistic double centuries in California.

The first stage was the Devil Mountain Double. Let me tell you that if you love climbing, you might not after doing this ride. What does it involve? Going up two of the Bay Area’s county summits—Mt. Diablo and Mt. Hamilton—along with not-so-trivial climbs through Morgan Territory, the Altamont Pass, Patterson Pass, and Mines Rd., for starters.

All that only takes you to Mile 150. And it is then and there—with already 14,000′ of climbing over and done with—you go up Sierra.

Being asked to go up a 1,800′ climb in just 3.6 miles after having ridden 150 really hilly miles would be considered cruel and unusual punishment in some capitals. Yet, here were 80 or so cyclists who had voluntarily paid hard-earned dollars to do this. This may lead one to question the mental intelligence of ultramarathon cyclists.

Some of these same-said cyclists were undoubtedly questioning their own state of mind and courage as they rounded the corner of Piedmont Rd., only to be greeted by what I had dubbed in a report of the 1999 Devil Mountain Double as “the Monster”. Now, I have done a couple of other climbs in the state/nation/world that are about as steep (an average of 9.6%), but have yet to see one that matches the visual impact of the start of Sierra, which—right beyond a long stretch that is virtually completely flat (0% grade)—is a whopping 15%.

In fact, the mere sight of the Monster prompted some climbing-weary cyclists to dismount off of their bikes and start walking right before my very own eyes. I remained seated, but let me tell you something: I was hardly riding faster than these walkers.

My quadriceps and hamstrings cried out in pain as I pleaded with them to do their job. I tried to focus my thoughts on the next hairpin corner—one my leg muscles hoped would be the top, but in my mind, knew was far from it.

Actually, according to my friend Steve Wickland, some of these corners are even steeper than the start of the climb. That sounds plausible to me. In any case, by that point, even if the corners weren’t any steeper, they’d feel like it.

By the time I made it to the top, I felt a deep satisfaction, mainly, “Phew! I haven’t passed out yet!” Never mind there were still 45 miles to go and quite a bit of climbing left in the ride.

Conclusion

Since that day, I have been up Sierra Rd. a number of other times—with considerably fresher legs—and each time, I have been astonished at the toughness of the climb.

If you are doing the climb for the very first time, let the above and the following be a warning to you.

“We wanted to try to make the race hard with two climbs to go,” George Hincapie added. “But that climb was really hard. I wasn’t expecting it to be that hard.”

Hincapie is a pretty good authority. He ultimately won the stage.

Climb Statistics

- Start (bottom) of the climb: just beyond the southeast corner of Piedmont & Sierra Road in San Jose, just south of Milpitas

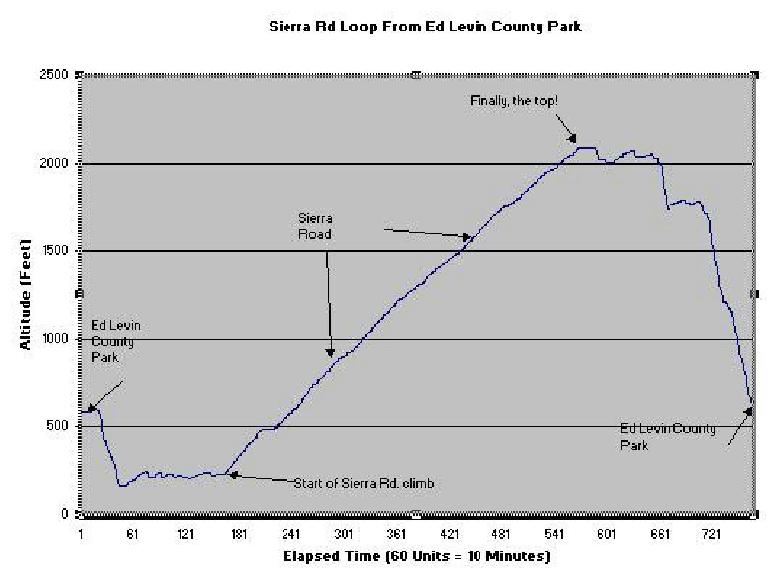

- Elevation gain: 1,800′ (source: Steve Wickland) or 1,843′ (source: Joseph Shami; see eleavtion chart below). During the Tour of CA, commentators Paul Sherwin and Bob Roll were referring to the climb as 2,000′.

- Length: 3.6 miles (source: Steve Wickland)

- Average gradient: 9.6%

- Average gradient at the bottom of the climb: 15%

- Felix’s best time up Sierra Rd.: ~34 minutes

- Elite cyclists’ time up Sierra in Stage 2 of the Tour of California: ~22 minutes

Elevation Chart

Below is an elevation chart provided by Joseph Shami, who used a Suunto X6HR watch to record the data (click on the image to enlarge). As you can see from the plot, the climb is sustained with virtually no reprieve until the top. Thank you, Joe, for the chart!

There are 12 comments.

Hi, I've ridden up Quimby a couple of times and am thinking of trying Sierra. They would seem to be roughly equivalent climbs. How would you compare them? Thanks.

Regards, Richard Snow

Hi,

I like your story about Sierra - I heard a lot of people talked about the Sierra Rd - I used to walk up the Sierra but I found out that it take a long time to walk the loop - so I took up biking four months ago and I used Suncrest as a practice climb - I finally can climb Suncrest twice - Last week I decided to ride the Sierra. I found out that it is hard but feasible. I made to the top and down Caleveras in one piece. The view is exceptional beautiful during this time of the year. Green forever - not much traffic last Sunday. Saw the bikers from other direction. One was riding a hard tail MTBike without wearing the helmet ...

Hi -

Great info. I just moved to CA from Florida, (eek) and am getting back on the bike after about 5 weeks off. (Starting law school.) Well, on my third day back, I decided to try this road that looks like it kinda weaves up one of these mountains off in the distance. Well, without any research, I find myself climbing up Sierra Rd. Now, I didn't really know at the time whether the climb was that hard, or if I was just a huge sissy after riding on the flats of Florida for 3 years. Well, thanks to your story, I know that I'm not quite as much of a sissy as I had thought! (Though, still a sissy) I did make it up in about 30 mins, which is great, but nearly wet my pants on the descent. Holy cow, was that scary.

Richard:

Yes, the West side of Quimby (from Ruby ave) is very similar in difficulty to Sierra. It's longer and has a really hard section at the top, but about equivalent in difficulty. Give it a shot if you haven't already.

Try Welch Creek rd if you're feeling strong...

[...] Felix Wong’s Blog on his Sierra Road Encounters [...]

I climbed Sierra Rd last week in a rented Mustang. I am still getting the shakes! Near the top there are many blind one-lane twists leaving one hoping there is oncoming traffic. If I go back it will be on foot.

Just did 10 repeats up and down Sierra Road last month. I had 32 ascents for the month of August. It's my training ride. Did the Devil last three years in a row and it was tougher than doing the 10 repeats. The temp got up to 107 on the day I did the repeats though and that made it tough. I had a standard for those three Delvils but now have a compact and that helps.

Brian

I just did 16 repeats up and down Sierra Road in one day. Started at 5:35am in the dark and ended at 8:23 pm. just as the sun set. Toughest thing I ever did. Tougher than the DMD!!! At 100 miles I had over 25,000 feet of climbing. The reason I went for 16 repeats is because I wanted to top the elevation of Mount Everest. It was hot in the upper 90's in the late afternoon. I was alone all day but did the last climb with this rider from SJ Bike Club named James Thompson. It really helped to have someone to talk to on that last climb. Actually, the descents were very tough toward the last few. My wrists and hands were killing me. I have carbon rims with cork pads and that made it tough.

I did this ride with a compact double 34-28 gear.

Here are the ride stats:

Trip 118.09 miles

Elevation Gain 29,200 feet (based on ride profile of 1,825 per climb) My barometer came in at 28,406 feet elevation gain for the ride.

Actual time pedaling 12 hours, 46 minutes.

In the future, I would love to read that someone topped my effort but I think it would really take a tough nut to do so.

Brian Canali

Ok- just climbed Sierra road 17 times in one day. 31,000 feet of climbing in one day. Started at 5am and finished at 9pm. Total distance was 123.8 miles. Tired now.

Absolutely amazing, Brian! Noting this on the Sierra Rd: 16X in One Day page!

[...] had planned to climb Sierra Road after the descent, but only if he felt fresh. Sierra Road is known as one of the most relentless [...]

I have taken my bike go up it once. Most time is walking with bike. Little time is riding up. Takes over 1.5 hour to get summit