1999 Reynolds Wishbone #35

In the new millenium, my ultramarathon cycling career will continue partly on a recumbent! My interest in these speed-machines dates back to 1997, when during my last quarter at Stanford University, I began designing a ‘bent of my very own. Unfortunately, I never finished that project. However, three years later, I have just building a recumbent based on George Reynold’s semi-low racer frame, the Reynolds Wishbone SWB (short wheelbase).

The advantages of a recumbent over a traditional upright bicycle include a more aerodynamic and comfortable riding position, arguably better safety, and typically higher attainable cruising speeds on flats and downhills. All of the human-powered land speed records have been achieved on recumbents. Their main Achilles Heel is climbing, although some riders, including famed Race Across America rider Pete Penseyres, claim that they are at least as fast on their recumbents as their upright bicycles up to grades of 10%.

Alas, after years of doing double centuries on my regular bike and recumbent, I cannot climb nearly as well on my ‘bent as on my “upright” road bike. Actually, on short and non-steep climbs, I climb about the same. In fact, on some rolling courses, I ascend faster on the recumbent just because the entry speed is higher from the downhill. For long or steep climbs, however, there is no doubt in my mind the recumbent is at a big disadvantage. See analysis below.

Comparison of Recumbent vs. Upright Bicycle

Below are excerpts from an email I wrote in March 2003 on this topic:

Thanks for your message. I have always meant to post something on my website about this topic, but it has been way down there on the to-do list. Anyhow, here’s my honest opinion, with some time comparisons for the same rides.

Let’s start out with the time comparisons.

- 1998 Solvang Double (Cannondale): 14:10

- 1999 Solvang Double (Cannondale): 14:26

- 2000 Solvang Double (Reynolds): 12:12 (my quickest double ever)

The Solvang is a flat/rolling course, with notoriously strong headwinds when riding northbound (which is like 33% of the time). There is only one semi-long hill of maybe 15 minutes at the end. I definitely felt that the Reynolds was quicker on this course, though probably not as much as the time difference suggests. This is because I was so comfortable sitting on a “real” seat on the recumbent and stopped much less!

The next time comparison was the climb up Mt. Diablo in Northern California. It goes up 3800 feet in 11 miles—a 6.5% average grade.

- in the 1999 Devil Mountain Double (Cannondale): 1:25

- in the 2000 Devil Mountain Double (Reynolds): 1:35

So here the recumbent wasn’t TOO much slower, but it is definitely at a disadvantage on the climbs.

To illustrate, here is another example: the Knoxville Double, with >12,000 feet of climbing over 200 miles (320 km), and hills seemingly everywhere:

- 2000 Knoxville Double (Reynolds): 19:05 (stopped a lot due to riding with someone else)

- 2001 Knoxville Double (Reynolds): 17:35 (did not stop much)

- 2002 Knoxville Double (Cannondale): 14:12! (stopped about the same amount as in 2001 or maybe even more due to getting 4 flat tires)

I was in better shape in 2002 than in 2001, but any way you look at it, this ride pretty much conclusively made me concede that I prefer to do any ride with significant hills on my Cannondale.

Last example: the Death Valley Double (200 miles, 9000 feet of climbing, with most climbing concentrated in a 25-mile stretch):

- 1997 Death Valley Double (Cannondale): 15:30, after riding a 5:30 first 100 miles (fastest century ever)

- 2002 Death Valley Double (Reynolds): 15:25

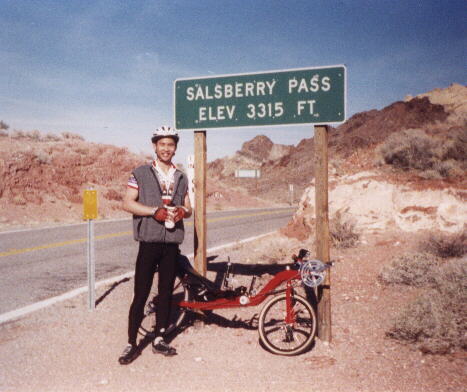

This course features Salsberry Pass, which is 16 miles long, and took me two hours to climb the front side on the recumbent. and then one hour to climb back up the back side. The rest is flat with nothing exceeding, say, a 3% grade. I thought it would be a good recumbent course, and indeed, my time was fair (better than my 1997 time in fact, but in ’97 I had multiple flat tires plus an injured ankle, etc., in the second half), but after finishing the ride I really felt I would have been faster on my Cannondale. This is because I was so wasted after going up Salsberry Pass twice that my legs had nothing in them to take advantage of the flat course afterwards.

In conclusion, for a flat or rolling course and assuming no drafting, the recumbent is faster. But for a course with either long or steep hills, it’s slower than a diamond-frame bike because 1) you are always using the same set of muscles, whereas on a regular bike you can alternate between standing and sitting and give your muscles a break, and 2) at 26 pounds (fairly light for a recumbent), it’s about 6 pounds (2.7 kilograms) heavier.

The Reynolds Wishbone has a reputation for being a good climbing recumbent, so other recumbents might be even more disadvantaged on long climbs.

Ken Gould’s Impressions of the Wishbone

I communicated with another owner of a Reynolds Wishbone recumbent in September of 1999 before purchasing mine. Below were his impressions.

Felix,

My best & easiest response is to forward a message that I have been trying to post (without success to date) on the RemarQ Internet recumbent discussion group at alt.rec.bicycles.recumbent. If after reading the message you have additional questions, please send another email & I will try to respond promptly.

I am the proud & very satisfied owner of a Reynolds’ Wishbone Recumbent. I’ve had the bike about 1 month now & am of the opinion that recumbents just don’t get any better than the Wishbone.

The bike is fast! I cruise easily @ about 22 mph & can sustain 23 – 26 mph for as long as 1 ½ hrs. (the longest ride to date) with a little more effort. An all out sprint on the flat takes me to 29 – 30 mph. My upright riding friends (most of whom are pretty strong bikers) hate the thing. Coming off a medium sized hill the other day a strong upright rider alongside said, “this is the only way I can possibly stay with your bike now, getting a good boost coming down hill.” My response, “I am not trying to show off, but watch this.” With that I shifted one gear, began putting more power to the pedals & within a short period of time was close to ½ mile ahead of my friend & hitting 38 – 39 mph. This is on the flat, albeit coming off the boost from the downhill. I also came in second in a 200 + biker 48 mile ride/race only to overhear the policeman who drove the escort vehicle say, “the guy in first (upright) looked like he was working really hard, but that guy in second just seemed to be asleep on his sofa.”

The design of the Wishbone has indeed evolved over time (my impression is that it just keeps getting better). Kent Peterson at one point described the bike as “crude.” My bike is pretty damned refined in appearance – very sleek looking. It is the first recumbent I have seen that has the upright riders saying “wow” rather than “that thing looks weird & cumbersome.”

Since my primary interest in recumbents is the speed factor, George Reynolds tried to cut a little here & there (even lower seat angle, I believe) to accommodate that interest. My bike may appear more refined than George’s demonstration bike that I test drove or Kent Person’s bike because mine has a burgundy powder coat rather than the nickel plating which I believe is George’s standard.

In addition, I added the following upgrades which I strongly recommend: thumb shifters (far superior to the standard grip shifters); a nine speed rear hub (diminishes the significance of deciding to shift from one gear to another since the step increase/decrease is less); and a Shimano XTR rear derailleur.

I also painted the metal bracket that holds the handle bars in place (otherwise a somewhat unattractive unpainted metal) a gloss black & covered the steering rod (also unattractive – a threaded metal rod) with black, pliable plastic pipe having a diameter just slightly greater than the rod – slid the pipe over the rod. I believe the pipe is designed for use in lawn sprinkling systems.

I use a Rhode Gear mirror of the type that fits in the end of the handle bar (with the Wishbone it makes a right angle bend at the joint as it comes out of the handle bar). George’s bikes are so cleverly designed with such close tolerances for various features that some options are limited or not available.

Yes, George uses Astroturf for the seat. He feels that the seat angle is so low that the Astroturf prevents the back from sliding up the seat when pressure is applied to the pedals. I too had some irritation from the turf blades on my back & wasn’t wild about the negative effect the turf had on the appearance of an otherwise great looking bike. Solved the problem by placing a chamois (sold for washing cars) cut to size on the seat & seat back & then covering that with a black terry cloth towel, also cut to form, wrapped around the seat & back of the seat & held together in back with safety pins & on the sides with small bolts that came in place on the sides of the bike set. The black terry cloth looks great against the burgundy frame.

I have had no problem with the laid back, fairly extreme seat angle – at least no neck problem. One reason I have had no problem with the seat angle may be that I rode a Vision R40 with the seat fully reclined for 3 years prior to arrival of the Wishbone.

After my first long ride on the Wishbone I did experience some pain in my butt & put a Thermorest pad on the seat for several rides after that. However, I think the problem was just one of conditioning my gluteus muscles for the different seat. I have since abandoned the pad & have had no additional problems.

I was initially attracted to the Wishbone because I had attached mountain bike bar ends vertically to my Vision’s handle bars & mounted the shifters & brake levers on the bar ends – really liked that arrangement. It is much the same as the setup on the Wishbone. I strongly believe that the Wishbone’s USS with the vertical mount position for the handle bars is the most aerodynamic & performance effective position. The vertical bars allow the upper body to apply force to the pedals as you pull in opposition to the bars.

I also have a testimonial as to the strength of the bike. After my third ride, I put the bike up on the car roof rack to go home, started the car & then turned out of the parking lot only to hear the thud of metal on the street. I hadn’t gotten the bike on the rack tightly enough & it fell off the top of the car & onto the street. I was crestfallen thinking I had probably destroyed my new bike. Total damage: right side crank & top chain ring had to be replaced. Otherwise not even a scratch or bend to any other parts or to the frame. While the bike was in my LBS it received a lot of attention (in the words of the shop manager, “it turned a lot of heads”).

A question was raised about mounting a cyclocomputer. George welds a mount for the computer on the top of the water bottle cage located on the frame directly in front of the seat. A small bag for storing tools, tubes, etc. can be mounted under the seat back.

To the extent this might be a factor in evaluating the performance capabilities of the bike: I am 56 years old & am in pretty good condition. I ran track & cross country in college & continued running for 43 years until 3 years ago when my knees finally said, “no more pounding.” Have stayed in shape since then by riding bents.

Ken Gould